I have to admit to a bit of trepidation when I showed up at the door of Gerald Self's house/workshop. Granted, the man had been very congenial when we exchanged e-mails about the possibility of a visit to his shop, sending me documents informing me of the do-it-yourself kits he sold and the models he built himself, assuring me that he would not try to sell me anything, and insisting that there would be no charge for the visit. However, I was pretty certain he wasn't expecting a long-haired twenty-something year old to show up in jeans and a T-shirt. (My only excuse for being so under-dressed is that I have a large number of severe chemical sensitivities that make it extremely difficult to find dress clothes.) I found myself arriving a bit early, too, which made me concerned about the possibility of throwing his schedule out of balance. Fortunately, the personality that was revealed through e-mail very quickly asserted itself once he recognized me.

Once inside I couldn't help admiring the home. It was deliciously cluttered! A cluttered home is an indication of a well-furnished mind, after all. (Or so I tell myself!) There was a harpsichord in the middle of the room with sheet music and other documents strewn about on top of the case -- clearly his playing instrument -- and a spinet and a clavichord occupying separate corners of the room. I'm pretty sure I also recall a stack of records in one corner. I can't help but like someone who keeps a record collection.

Most of the harpsichords -- and by extension where most of the action took place -- were located in an adjoining room. The instruments displayed in this room were of various styles and time periods with a focus on French models, and were available for rental or demonstration purposes. He rattled off an impressive list of renters' names, some high profile. None less than Richard Egarr had used one of his harpsichords in a performance and commented quite fondly upon it. All instruments were by Gerald's hand and all were remade with scrupulous attention to historical details, right down to the paint jobs on the outer casings. The room was filled with diagrams, small stacks of photographs, and other materials that made clear his dedication to his craft.

His dedication and knowledge were made even more clear to me once he started his presentation on the history of harpsichords. Among other fascinating tidbits I learned that the reason for the high aesthetic quality of historical keyboard instruments is that the producers tended to work in guilds alongside more traditional woodworkers, painters, and printers, which gave them access to outside talent for painting the soundboard, or printing out a design to glue onto the bottom of the case for display purposes when the lid was open, or for simply finding quality wood or the tools to sculpt it. This information shines a light onto the wide range of talents required by a modern instrument maker producing reproductions primarily on his or her own. He also discussed the development of harpsichords over time, the influence of various regions upon builders in other areas (how German models influenced 18th century French harpsichords, for example), the development of tuning systems, matching the right tuning system and harpsichord with the right composer, stringing of the instruments, and other things I'm not qualified to write about.

One of the great joys of the visit was -- of course! -- getting to hear the harpsichords, and he was quite generous in this regard, punctuating various elements of the lecture by playing pieces on the instruments to show me distinguishing characteristics in tone, volume, decay time and an assortment of other elements that contributed to the unique sound of each harpsichord. I particularly enjoyed when he invited me to get 'under the hood' and take a look at how the harpsichord functioned, and explain how that differed from the workings of a piano. (Prior to that I practiced a policy of staying out of the way and not touching a damn thing!) He also gave plenty of details on the more artistic aspects of the job such as painting the soundboard and the outer casing of the instruments and did side-by-side comparisons with photographs of the originals.

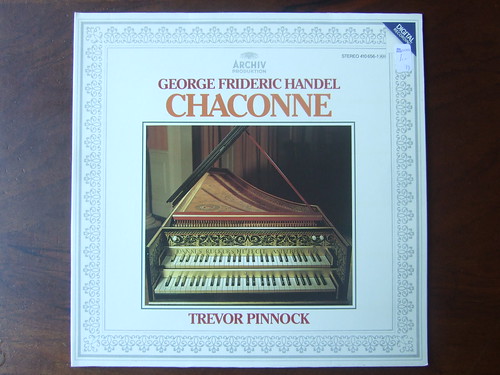

The final part of the tour took place in his garage, the formal 'workshop' where all the work was done. Upon entering I was immediately hit with a smell that will be familiar to anyone who has ever been in a shop that handles woodwork. It certainly helped generate a certain ambience, though it had some help from the rack of 'garage' cassettes hanging on the wall featuring...you guessed it...harpsichord recordings! There was also an LP cover posted at about eye level on a wall -- I assume for decorative purposes. If memory serves me correctly, it was this one:

While in the shop he showed me the skeletal beginnings of a couple of instruments he was building and explained to me the properties of a soundboard of a harpsichord and how that varies from a piano. This is, again, a subject I'm not qualified to discuss. (Perhaps I should have taken notes!) Once the presentation was over I asked a few questions about technical aspects of the instruments and then left as he was clearly very busy. I am grateful for his generosity in taking time out of his day to share his knowledge and his willingness to do it for free. For those who didn't catch it earlier, here is his website.

For those of you not familiar with the instrument, here are a few harpsichord recordings on YouTube:

- Ton Koopman playing the famous Prelude and Fugue in C major by Bach from the first book of the Well-Tempered Clavier.

- Pascal Dubreuil playing a movement from Bach's Partita No. 4.

- Pierre Hantai playing the first nine movements of Bach's Goldberg Variations.

- Michael Borgstede playing a movement from one of Handel's Harpsichord Suites.

- Pierre Hantai playing Scarlatti's Sonata No. K56

No comments:

Post a Comment